The Engineers Revenge: Managers Are Losing the Battle in Big Tech. Can we just get rid of them?

- Bitscrunch Avocoder

- Jan 26

- 4 min read

Updated: Jan 29

The Blind Community’s Perspective on Tech’s Latest Managerial Shakeup, spiced up with my own thoughts

Over a year ago, starting in 2023—the so-called "Year of Efficiency"—and extending well into the majority of 2024, Blind users eagerly embraced the narrative spun by Big Tech leaders: pit engineers against managers. As cheers erupted for slashing middle management, demoting VPs, and reassigning line managers to IC roles, some Blind users took it even further—targeting HR and even principal engineers. (Well, to be fair, engineers always disliked HR)

In 2022, Before his masculine energy times, Zuckerberg announced plans to cut more than 20,000 employees, taking a bold stance on flattening organizations and targeting middle managers with 3–4 direct reports as symbols of inefficiency.

Google and Amazon quickly joined the party: Google laid off second-layer managers up to VPs, while Amazon set ambitious goals to increase the IC-to-manager ratio by at least 15% across all managerial levels by the end of Q1 2025. This aimed to effectively eliminate both line managers and more senior roles. Amazon also codified these changes by updating its official Role Guidelines for managers, formally raising the required number of direct reports.

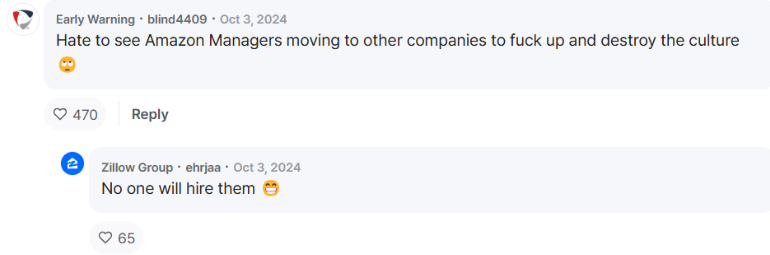

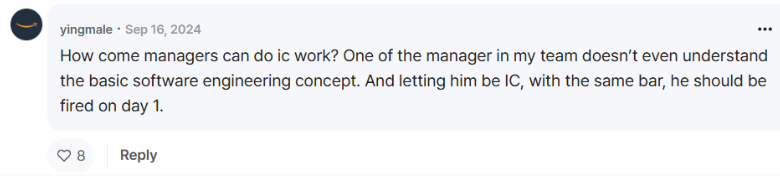

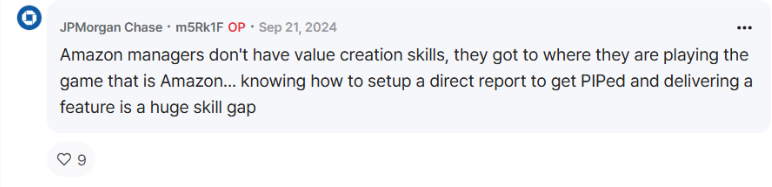

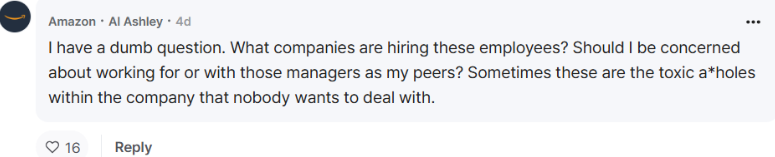

The Blind community swarmed to the narrative like flies on a fresh pie, supporting the move by claiming that their managers contributed little value, lacked real business understanding, had no technical skills, and merely "played the corporate game." They argued that most managers would be unable to hold onto their jobs if forced to transition into IC roles.

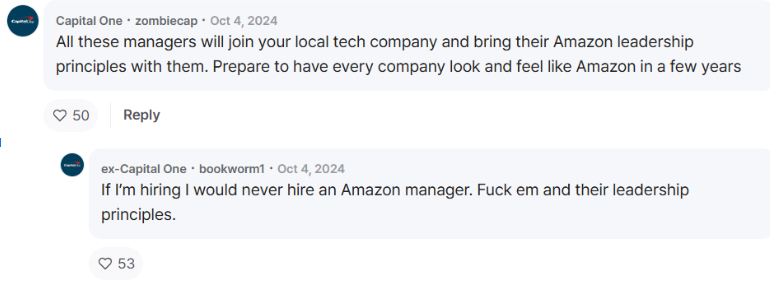

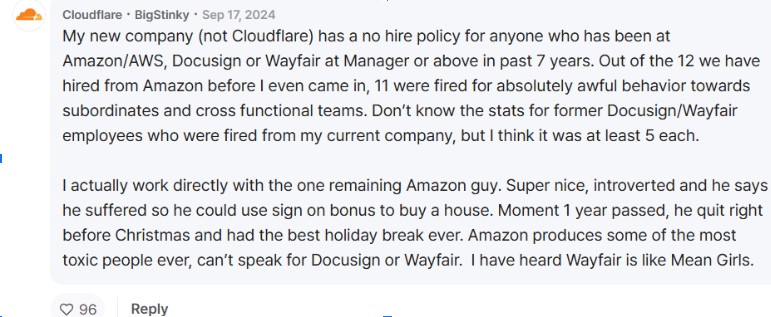

Amazon employees questioned whether anyone would even consider hiring those toxic, laid-off managers. Some even claimed that their companies had an unofficial policy of not hiring ex-Amazon managers!

What if we just let go of half the managers?

As a manager myself, I think it’s a question worth asking. If the goal is to cut costs and trim the "non-producing" layers in the company, why stop at a mere 15% IC-to-manager ratio increase, while getting rid of the remaining managers? Take Jensen Huang, Nvidia's CEO, as an example—he has nearly 60 direct reports. And it’s clearly working, pretty well too. So, why can't Amazon take a page from Nvidia's playbook and aim for a 20%, 50%, or even 100% increase in the ratio? Come on, show some ¨Think big¨ and ¨Frugality¨.

Well, even if you think your manager is technically incompetent, they’re supposed to be managing people’s performance. Managers are the ones promoting top-performing employees and addressing underperformance—either through improvement or, when necessary, elimination. At Amazon, managers spend a significant amount of time writing promotion documents (hopefully, they don’t need to spend much time preparing PIP plans). A great manager also invests a couple of hours each week collecting and delivering meaningful, actionable feedback to help their direct reports grow.

Delivering a quality promotion document with a real chance of being approved can take me an entire week. That’s the time it takes to review the employee’s draft, rewrite it (because, let’s be honest, even with the best generative AI tools, software engineers don't excel at storytelling or writing), gather feedback from providers, and then go through a couple of rounds of early reviews. All this happens before the big meeting with my Sr. Manager staff, where the promotion is either approved or denied.

Now, speaking seriously, increasing the IC-to-manager ratio could lead to talented employees missing out on timely promotions because their managers simply won’t have the bandwidth to focus on their development. At the same time, underperforming employees might overstay, continuing to drag down their teams. Without clear sticks and carrots, ICs will have less incentive to go above and beyond. They’ll probably leave to a place that provides the appreciation they deserve.

Another consequence of a massive manager let-go is that the remaining managers would need to deliver 15% (or 20%, 50%, or even 100%) more business value. While managers don’t directly deliver features themselves, they are responsible for ensuring their teams consistently deliver value—both in the short and long term. This involves proactively identifying and mitigating risks, as well as ensuring that the engineers owning the features are set up for success, deliver on time and meet the expected quality standards.

When a team misses its commitments, stakeholders—senior managers, program managers, or customers—often ping the manager directly, treating them as the "adult in charge" and demanding a plan. Similarly, when another team blocks or delays progress (hopefully for valid reasons) and the engineer leading the feature escalates the issue, the manager steps in to resolve it. So, does 15% more direct reports mean supporting 15% more features? Identifying 15% more risks? Unblocking 15% more engineers? If so, the outcome boils down to one of two scenarios: either stakeholders accept that managers will have less bandwidth to ensure smooth delivery for all features, or the organization’s culture and mechanisms evolve so engineers themselves take on 15% more responsibility, independence, and accountability.

Finally, to present a balanced view, I’ll be honest and acknowledge that there are managers with 2–4 direct reports who could undoubtedly take on more responsibilities. There are also managers who have recruited and built teams under them that deliver little to no customer value, profit, or cost savings—a phenomenon called "Empire Buildind" (as I learned in Blind) And, of course, there are managers with a "reasonable" number of direct reports overseeing productive teams that simply don’t contribute enough value themselves. Their managers are expected to manage their performance and, if necessary, push them out.

Let me know your thoughts in the comments. Can we truly have a self-managed team without a formal manager? Could AI step in as an effective manager? And who should take on the responsibility of optimizing a team’s delivery against business goals?

Also, let me know if there’s a topic you’d like me to cover—spiced up with some Blind community posts, of course. I’m thinking my next post could tackle The Ultimate Debate: What’s worse—having an "engineer" manager or a "TPM" manager?

Comments